A research project investigating how people’s attitudes towards material possessions altered in sixteenth-, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England is appealing for public help in analysing thousands of personal wills

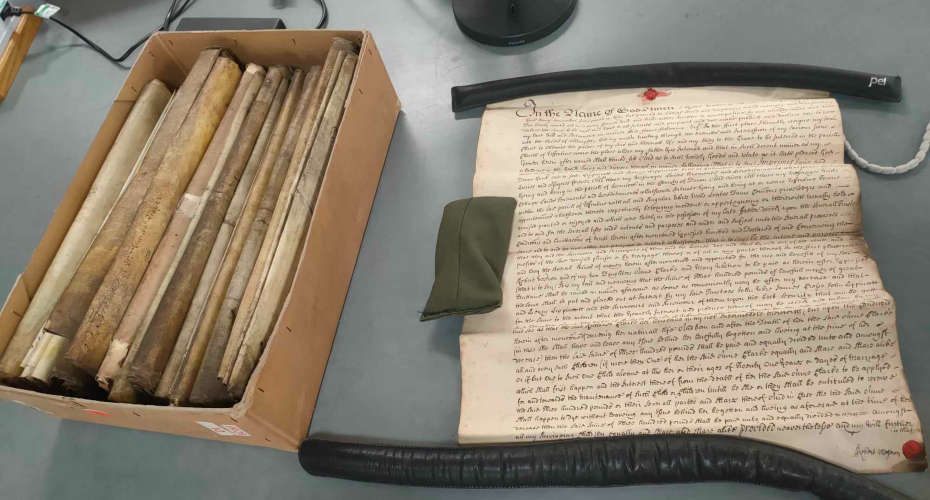

The Material Culture of Wills: England 1540-1790 is studying an unprecedented number of historic documents held by The National Archives to understand how material culture developed during an era of increasing commercialisation and trade.

The four-year project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust and led by the University of Exeter, is using specialist AI software to auto-generate transcriptions of 25,000 wills.

Now, researchers in the University’s Department of Archaeology and History are recruiting a team of ‘citizen social scientists’ who will check and verify the data and potentially highlight significant discoveries.

“Wills are the most common personal document to survive from before the modern period,” says Professor Jane Whittle, Principal Investigator on the project. “They provide evidence of not only what people owned in the past but, through their descriptions and bequests, how they thought about objects. The challenge, historically, has been how do you transcribe such a wealth of material – material which is often written in a manner that is difficult to decipher. Through a combination of technology and public enthusiasm, we’re hoping to meet that challenge.”

“Across these centuries most will-makers took the trouble to describe in detail some of the items they bequeathed to particular relatives and friends,” adds Co-Investigator Dr Laura Sangha. “For instance, Elizabeth Brickenell, a widow of Exeter, left a friend her third best petticoat in 1569, while in 1603 William Radcliffe of London left his sister ‘a gold ring with a picture of death’s head, for all her unkindness’. Bequests in wills thus provide evidence not only of what people owned, but also, by choosing objects to bequeath and describing them in particular ways, of people’s attitudes towards those possessions.”

Work on The Material Culture of Wills project began in November 2023 when the researchers recruited a small team of volunteers, who helped transcribe more than 400 pages – 26,000 lines of text – from a sample of wills.

Project partners at The National Archives used these transcriptions to ‘train’ a Handwritten Text Recognition model, assisting its AI to better decipher the handwriting.

But while the repetitive nature of the language used in wills suits AI analysis, the names of people and places, amounts of money and the details of some of the items bequeathed – details of especial interest to the researchers – are more challenging, and need to be carefully checked for accuracy. And that is where the community of volunteers will come in.

“We know there are keen historians and people interested in genealogy out there who will relish the chance to get involved in what is a ‘mass citizen social science’ project,” says Dr Emily Vine, Research Fellow. “Volunteers will be able to hone and improve their palaeography skills at the same time as contributing to the success of a cutting-edge research project. They can devote as much or as little time as is convenient, and they can fit transcription tasks in whenever they have a moment – on the bus or waiting for the kettle to boil.”

The Material Culture of Wills is using the Zooniverse platform to engage with the public, with Dr Harry Smith, Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University, designing and creating a bespoke project site. As new transcriptions are uploaded to the Zooniverse project area, so volunteers will be able to log on and review lines of text that have been selected for scrutiny.

The researchers estimate there could be as many as two million lines of text for verification – with four people needed for each single check.

“As each line is reviewed by the team, so we will feed these results back into the programme to improve its accuracy,” says Mark Bell, Senior Digital Researcher at The National Archives. “We hope that the legacy of this project might enable us to effectively open up other areas of the archive for analysis, generating new insight and knowledge.”

It is expected that the analysis phase will take a year to complete, and the results will be made available in an open database.

Special meeting called as election delay branded ‘deeply dangerous’

Special meeting called as election delay branded ‘deeply dangerous’

Rural MPs vow to continue to fight for farmers as controversial bill proceeds through parliament

Rural MPs vow to continue to fight for farmers as controversial bill proceeds through parliament

RNLI offers essential safety advice for cold water dippers this festive period

RNLI offers essential safety advice for cold water dippers this festive period